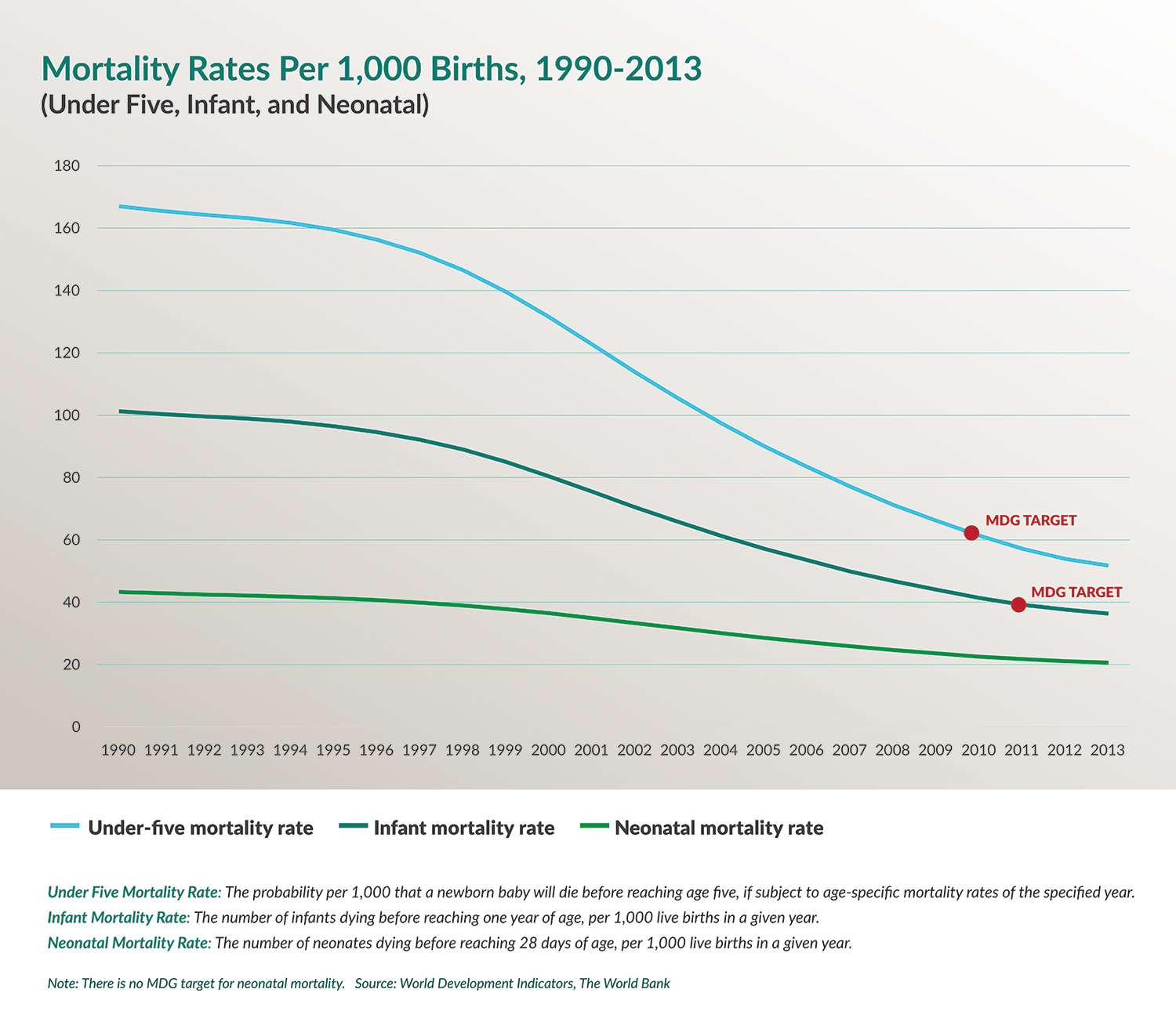

Over the last 15 years, the world has made considerable progress on reducing the mortality of children under the age of five. In sub-Saharan Africa, many countries are on track to meet the international community’s child health goals. The United States has supported maternal, neonatal, and child health (MNCH) programs for several decades, and these efforts have had a considerable impact on the lives of children throughout the region.

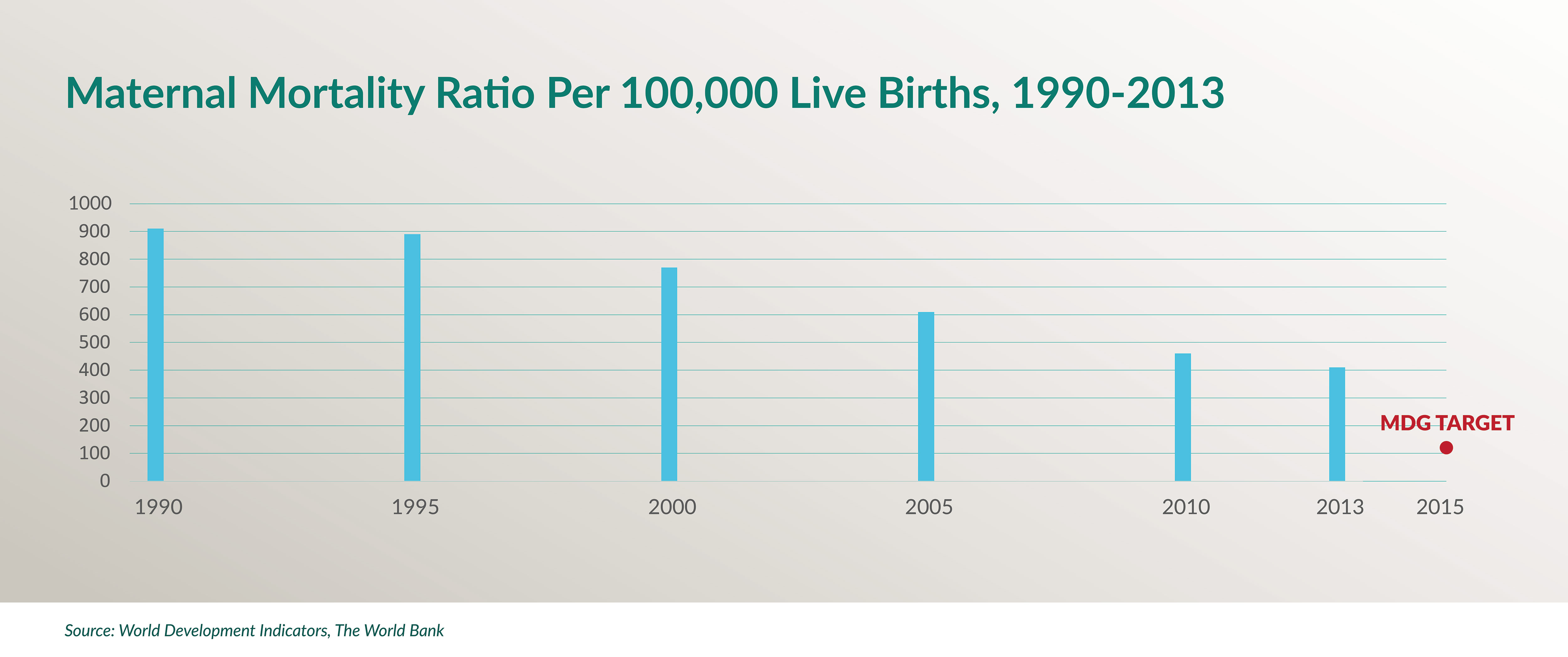

But making similar reductions in maternal and neonatal mortality has proven to be a much greater challenge. 1

What lessons can be learned from sub-Saharan Africa’s success in improving child health? What role can the United States play in building on those successes? What can be done to address the persistent challenges related to maternal and neonatal health in sub-Saharan Africa?

The experience of the United Republic of Tanzania in addressing maternal, neonatal, and child health challenges offers important examples to consider in answering these questions.

TANZANIA IN FOCUS

The United Republic of Tanzania was formed in 1964 after the islands of Zanzibar gained independence from the United Kingdom and united politically with the mainland, Tanganyika. Tanzania is a low-income country with a population of more than 49 million. Over 70 percent of the country is rural. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s largest city, has a population of about 4.5 million.

Health in Tanzania

In Tanzania, the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MOHSW) oversees public health policy and program implementation for the country’s population. The country is divided into 30 regions, each of which has some level of autonomy in managing hospitals and providing health services, although all must follow national health policy and report health data back to the MOHSW.2

The point of entry for mothers and children into the public health system is the community-level dispensary, where patients can receive exams, seek advice from a clinical officer or nurse, and procure medicines, medical supplies, and immunization services. Some dispensaries are equipped for labor and delivery; many offer HIV treatment options and services for the prevention of mother-to-children transmission (PMTCT) of HIV. For more comprehensive services or to consult with a physician, however, mothers and their children must visit a health center, which may serve several communities and typically offers a broader range of services than the dispensary.

Most people access health services at facilities without comprehensive treatment options.

Patients who arrive at dispensaries or health centers with more complicated cases are sent to the district hospital or regional referral hospitals. Particularly challenging cases may be sent to one of a handful of specialized national referral hospitals in Dar es Salaam. Those patients who live closer to a referral facility than a dispensary, and those who prefer to visit a more distant health center or district hospital because they believe the services will be of higher quality, often bypass community-level facilities altogether.

More than 70% of Tanzania's population lives in rural areas. Accessing health services at the community level can be a challenge.

In recent years, Tanzania has realized significant gains in child health and has already met its millennium development goal (MDG) target of reducing the mortality of children under the age of five by two-thirds since 1990. Particularly noteworthy achievements that contribute to this improvement include strong progress in extending vaccine coverage in all regions and successful activities to prevent and treat malaria among children.3

However, newborns account for 40 percent of deaths among children under the age of five. And the maternal mortality ratio has fallen only slowly. 4

Enlarge

Tanzania’s more modest achievements in reducing maternal and neonatal deaths are due in part to inadequate infrastructure, a lack of trained health workers in the most remote areas, and limited availability of necessary commodities, including supplies for facility-based childbirth and blood in the event of postpartum hemorrhage. Compounding these challenges are Tanzania’s relatively high total fertility rate of 5.3 and low national contraceptive prevalence rate of around 34 percent.5

The government of Tanzania has articulated ambitious plans to improve the population’s access to health services. Its strategy includes aggressively training and deploying health workers and bolstering domestic financing for health through a national health insurance scheme.

TANZANIA PRIORITIZES MNCH

In part due to its failure to meet the MDG target of reducing maternal mortality by three-quarters by the end of 2015, the government of Tanzania has recently prioritized MNCH through the launch of two new government programs: the Sharpened One Plan and Big Results Now. It has outlined a three-pronged approach for ending preventable deaths of women, newborns, and children: providing voluntary family planning services, improving quality care at birth, and continuing progress on child health.6 These efforts concentrate on serving regions that face the greatest challenges and are intended to focus the attention of national, regional, and district-level authorities on improving maternal, neonatal, and child health outcomes.

(left) Health care workers attend to women in labor in the Mnazi Moja Health Center labor ward. The Mnazi Mmoja Health Center, located in Dar es Salaam, provides outpatient health services to the 634,924 citizens of the Ilala municipal region. This facility performs an estimated 300 to 360 deliveries per month. (right) Mother and child in the Magu District Hospital. This 150-bed facility operates in a catchment area of 299,759 million people.

In April 2014, the Tanzanian government launched the Sharpened One Plan aimed at reducing maternal, newborn, and child mortality.7 The plan was developed following a 2013 review of the country’s 2008–2015 National Road Map Strategic Plan to Accelerate Reduction of Maternal, Newborn and Child Death, also known as the One Plan.

The Sharpened One Plan emphasizes accelerating progress in Tanzania’s Lake and Western zones, where progress has been particularly slow. It focuses on strengthening health systems in rural and underserved urban areas to increase access to reproductive, maternal, and child health services for women and girls in the most vulnerable communities.

Sharpened One is a costed plan covering the 500-day period until the 2015 MDG deadline to accelerate the reduction of maternal, neonatal, and child deaths. It focuses on five strategic areas: geographic vulnerability, high-burden populations, high-impact interventions, enabling environment, and accountability. Prioritized interventions aim to expand access to safe deliveries and increase family planning users in the Lake and Western zones; reduce stock-outs of maternal, neonatal, and child health commodities at the facility level; and improve accountability through the use of tools such as the Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health scorecard. Through this scorecard, regional commissioners (who are similar to state governors in the United States) are required to submit quarterly reports showing the percentage of women using contraceptives; the percentage of pregnant women attending antenatal clinics; and the percentage of women who deliver their babies in the presence of a skilled attendant.

In 2013, the government of Tanzania launched a multisector development strategy—known as Big Results Now (BRN)—to guide its efforts to reach middle-income country status during the next decade. Modeled on the Malaysian development plan called “The Big Fast Results Initiative,” the Tanzanian program initially focused on six priority areas: energy and natural gas; agriculture; water; education; transportation; and mobilization of resources.8 In October 2014, health was added as a seventh area of emphasis.9

The health-related component of BRN identifies four priorities for the health sector: human resources for health, system management, commodities management, and reproductive, maternal, neonatal, and child health. Strategies will include improving community outreach about and demand for basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric and newborn care services; upgrading facilities to offer these services; and expanding voluntary blood donation services to address needs associated with the expansion of emergency obstetric care.10 As with the Sharpened One Plan, the Lake and Western zones are the focus of these efforts.

The government has set a goal of reducing maternal and neonatal mortality in key regions by 20 percent by June 2018. 11

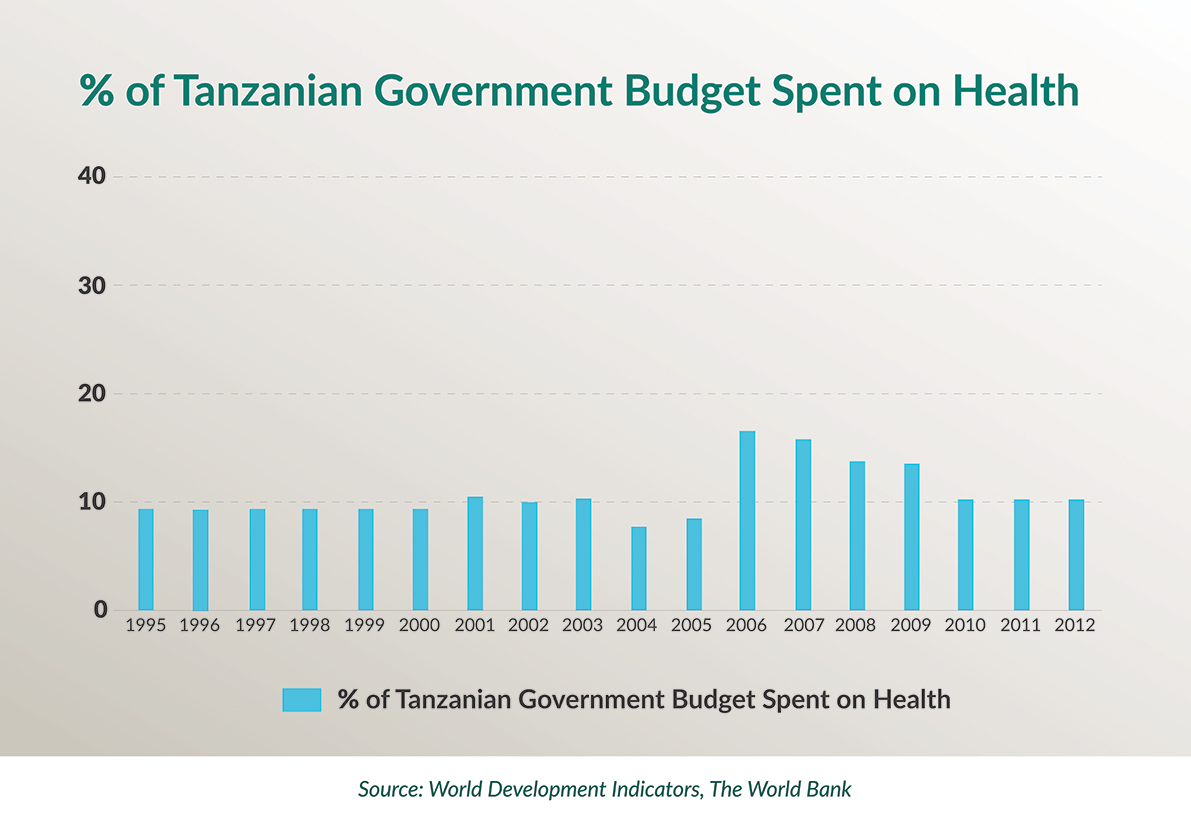

Despite its ambitious health goals, public spending on health in Tanzania has remained low, accounting for only 8.1 percent of the overall government budget. In 2015, the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare estimated a funding gap of $169.5M for reproductive, maternal, neonatal, and child health services alone.12 At the same time, the World Bank reports that external resources as a percentage of the total expenditure on health in Tanzania increased from 11.3 percent in 2002 to 38.5 percent in 2012.13

According to a recent assessment, realizing the Big Results Now MNCH goals will cost US$66 million.

As the government of Tanzania determines how best to finance its MNCH initiatives, it has invited bilateral partners and multilateral agencies to align their programming with and provide support for the Sharpened One Plan and Big Results Now.

SUPPORTING TANZANIA’S MNCH GOALS: AMERICAN DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE

The U.S. government has maintained bilateral relations with Tanzania since 1961, when the mainland, Tanganyika, achieved independence from the United Kingdom. U.S.-funded development assistance programs began shortly thereafter. The U.S-Tanzania Country Development Cooperation Strategy for 2015–2019 identifies women and youth empowerment; sustainable, inclusive, broad-based economic growth; and improved democratic governance as overarching goals, with work on health viewed as integral to each of them.

IN DETAIL: U.S. GLOBAL HEALTH PROGRAMS

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lead U.S. initiatives in Tanzania. The Peace Corps and the Department of Defense’s Walter Reed Army Institute of Research play important roles in the areas of training and research. The United States participates in working groups and other mechanisms to coordinate efforts across agencies and with the Tanzanian government and other partners.

In 2014, overall spending by the United States on health activities in Tanzania reached more than US$450 million.

PEPFAR

Of U.S. health assistance to Tanzania, 62 percent is channeled through the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), totaling more than $2.4 billion since 2004.14 PEPFAR, the largest global health initiative dedicated to a single disease, was established in 2003 to support HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment programs in developing countries. Under the leadership of the Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator, PEPFAR is implemented by U.S. government agency offices, including USAID, CDC, the Department of Defense, and Peace Corps, as well as by U.S. embassies in developing countries.

PEPFAR-funded activities that support MNCH include scaling up prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) programs and pediatric HIV services.15 The Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator reported that in 2014, thanks to U.S. support, 65,604 HIV-infected pregnant women in Tanzania received antiretroviral drugs to reduce the risk of infecting their babies with HIV during pregnancy and delivery.16

The United States has recently announced a strategy shift (called PEPFAR 3.0) for responding to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in collaboration with partner countries, including Tanzania. Under this new approach, PEPFAR will maximize its impact by using improved data to target populations at greatest risk, in areas of greatest HIV incidence, with evidence-based interventions.17

USAID

The USAID mission oversees the majority of U.S.-supported health activities in Tanzania. In 2014, the mission’s funds for health programming totaled US$273 million (including PEPFAR funds channeled through USAID). Several distinct program areas contribute to MNCH improvements.

Direct funding for USAID maternal and child health programs totaled US$12 million in 2014, and activities to strengthen immunization services received an additional US$1.2 million.

The President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI), which supports maternal and child health through its focus on indoor residual spraying (IRS) and preventing malaria infection, was funded at US$45 million. Also, in 2014, USAID funding for voluntary family planning activities, which contribute to maternal health through emphasis on healthy timing and spacing of pregnancies, totaled US$26 million.18

Tanzania is one of 24 MNCH priority countries under USAID’s effort to address preventable maternal and child death. The new USAID Maternal and Child Survival Program (MCSP) runs programs with the overarching goal to end “preventable child and maternal deaths within a generation.”19 MCSP activities in Tanzania include working with MOHSW to “improve the environment for RMNCH services through technical leadership and coordination; strengthen key health systems to deliver quality RMNCH services; strengthen the involvement of civil society; support institutions in RMNCH; and improve uptake of innovations.”20

Enlarge

CDC

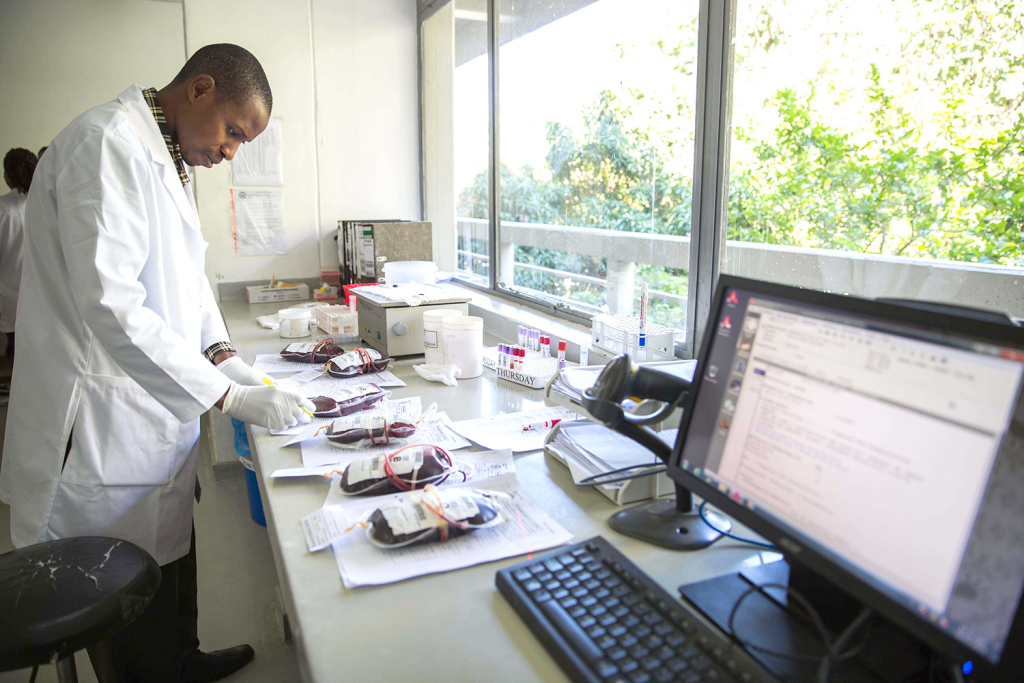

CDC provides the government of Tanzania with technical assistance on early infant diagnosis of HIV, PMTCT programs, and Option B+, the World Health Organization-recommended program under which all HIV positive pregnant women are offered antiretroviral therapy (ART) for life.21 CDC provides technical assistance to the MOHSW in assessing vaccine programs and has worked closely with the ministry to establish the National Health Laboratory Quality Assurance and Training Center. CDC also supports the government of Tanzania’s efforts to strengthen and ensure the safety of blood transfusion programs, an important element of postpartum hemorrhage care.

Technicians in laboratories at the Kabila Health Center (top), Bugando Medical Center (bottom left), and National Health Laboratory Quality Assurance and Training Center (bottom right)

Other U.S. Support

The Peace Corps contributes to U.S.-supported maternal, neonatal, and child health programs through the PEPFAR-funded Global Health Service Partnership, which places seasoned, professional obstetrician/gynecologists, nurse-midwives, and pediatricians in education and training facilities to support the professional development of Tanzanian health care providers.22 The Walter Reed Army Institute of Research-Tanzania, through the U.S. Military Health Research Program, also facilitates programs related to HIV vaccine research and service provision, including PMTCT and pediatric HIV programs.23

U.S.-Supported Public-Private Partnerships:

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and

Malaria and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance

Several global public-private partnerships that the United States supports are also actively engaged on MNCH issues in Tanzania. These include the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria, as well as Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. The United States is the largest bilateral donor to the Global Fund, which has provided almost $1.3 billion to Tanzania since 2003.24

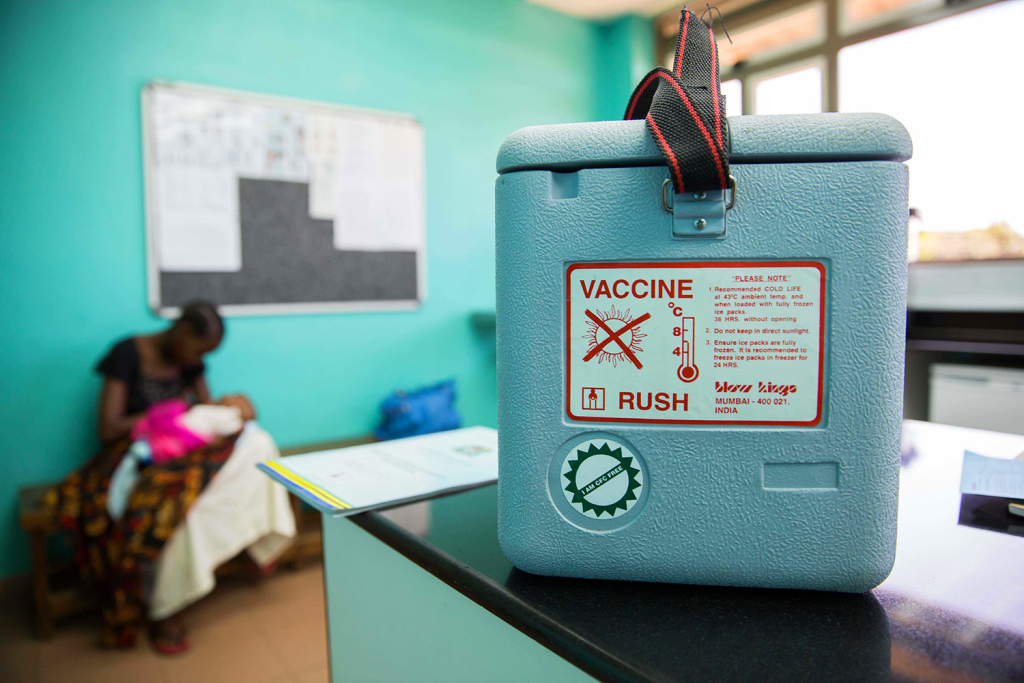

Child receives a vaccine at the Baylor Children’s Foundation in Mwanza.

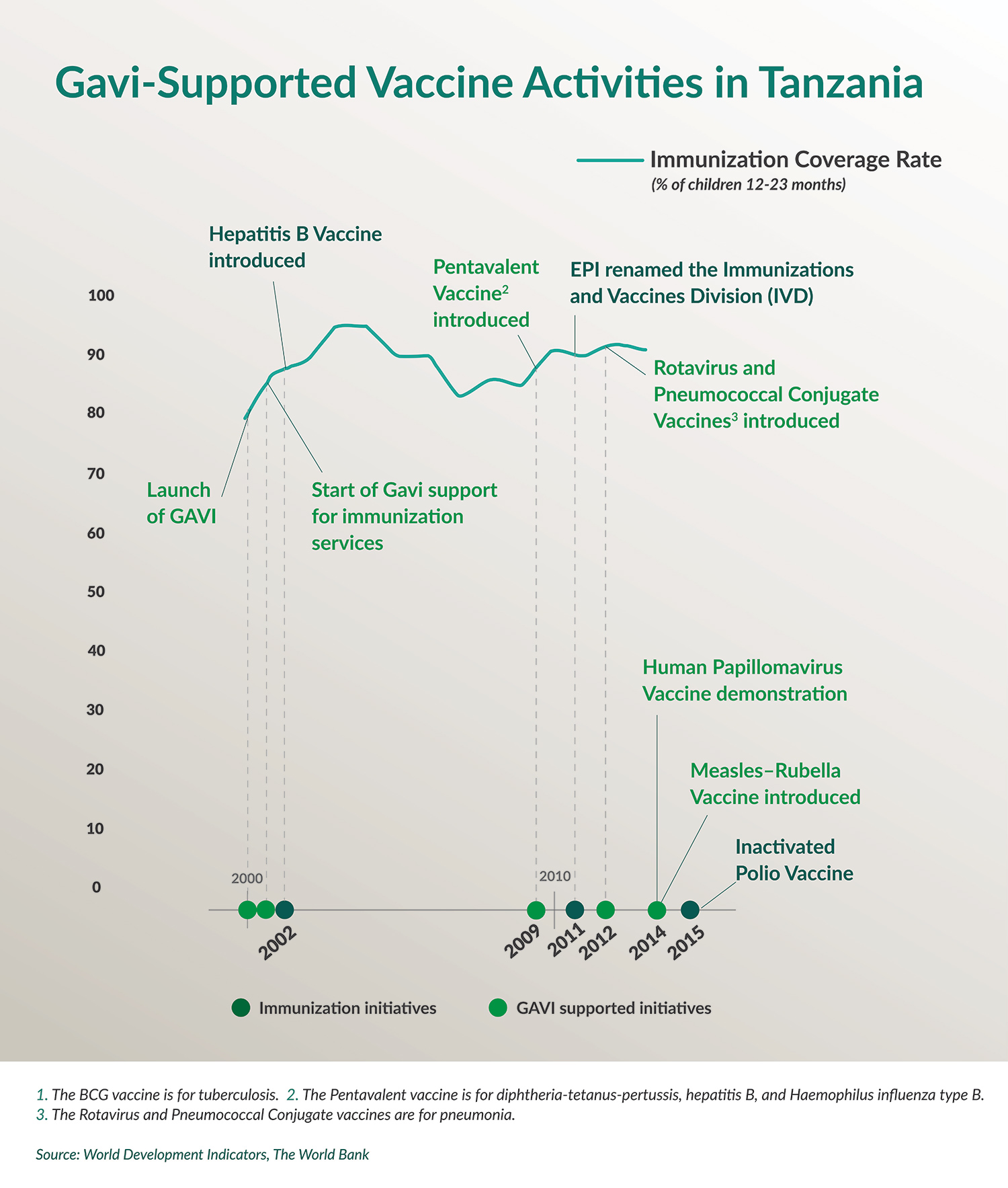

Since 2001, Gavi has supported the introduction of new and underutilized vaccines to prevent childhood illness, along with grants for strengthening health and immunization systems. The United States is among the top five donors to Gavi. The Gavi total disbursement to Tanzania, through February 2015, was nearly US$275 million. Classified by the World Bank as a low-income country, the government of Tanzania contributes 20 cents a dose, for a total of US$14.8 million since the partnership began funding work in the country in 2001.25

CSIS DELEGATION OBSERVATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In February 2015, the CSIS Global Health Policy Center led a delegation to Tanzania to better understand the factors in sub-Saharan Africa contributing to improvements in child health, on the one hand, and persistent challenges related to maternal and neonatal health, on the other. The delegation was particularly interested to understand the ways in which the United States government has supported work on MNCH in Tanzania in the past and how efforts might be strengthened or enhanced in the future.

A Look at the Mwanza Region

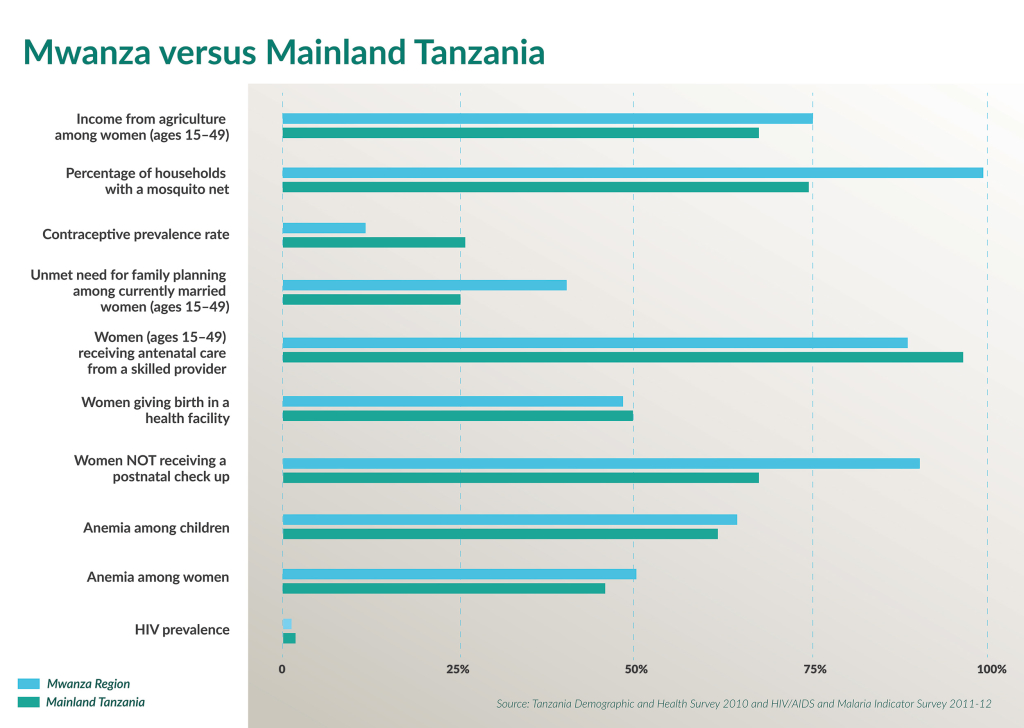

A focus of the delegation was a visit to Mwanza region, located on the southern shore of Lake Victoria. Mwanza is part of the Lake Zone, which has been identified by the government of Tanzania as an area of emphasis for MNCH activities due to its challenging indicators. Mwanza has a population of about 600,000 and is an important commercial center in East Africa. For decades, fishing and fish exports have supported a strong economy in the region, which also serves as a trade hub and point of access to neighboring countries Uganda, Kenya, Rwanda, and Burundi. Gold mines employ laborers from the region and, because of Mwanza’s proximity to Serengeti National Park, tourism plays an important role in the area’s economy.26

As of 2013 more than 75 percent of women and 70 percent of men in Mwanza were working in small-scale agriculture and living on less than US$1 a day.

Mwanza is a largely agricultural region.

The Mwanza region encompasses at least 60 islands, making access to health care difficult for many people whose livelihoods depend on the lake. Many of Mwanza’s citizens work in the fishing industry and frequently migrate to follow fish stocks at least part of the year. At just 11.7 percent, the contraceptive prevalence rate in Mwanza is extraordinarily low. On the other hand, the region’s HIV prevalence is 4.2 percent, slightly lower than the average for the mainland.

THREE KEY OBSERVATIONS

The following comments and recommendations are drawn from the delegation’s observations over six days of site visits and meetings with Tanzanian and U.S. officials, representatives of nongovernmental organizations, health care providers, and patients.

1.) The United States is investing resources in critical training programs and mentorships for improving maternal and neonatal health, but the needs in Tanzania—particularly at the community level—remain great.

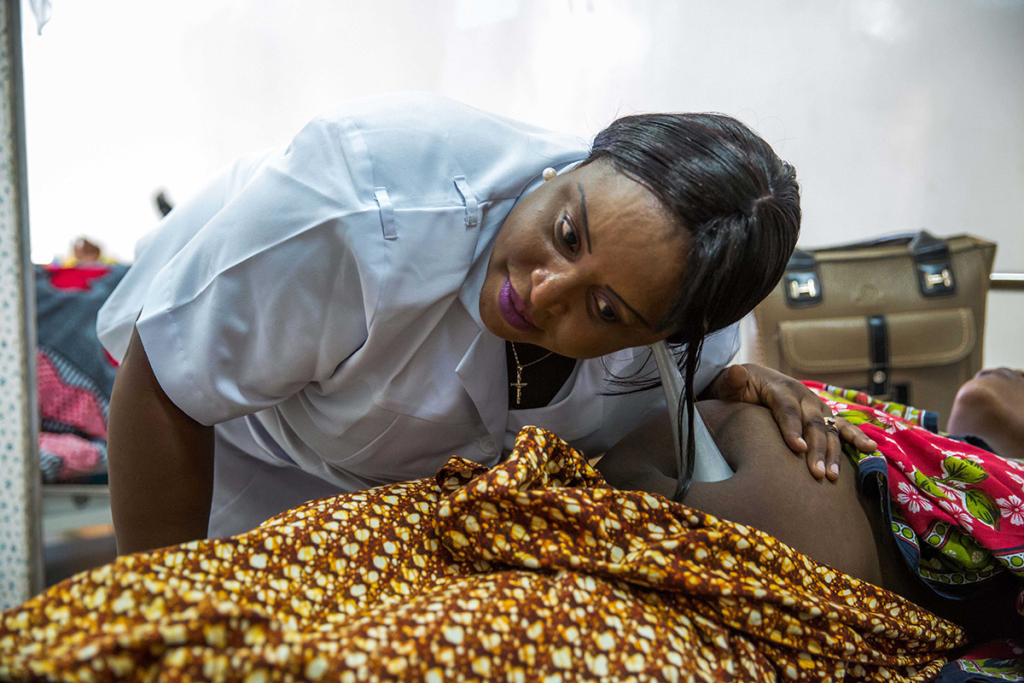

Accelerating progress on maternal and neonatal health will depend on raising the skill level of care providers so that they can recognize problems during the antenatal period and at the time of delivery and either respond with the appropriate care or quickly refer patients to another facility. At the same time, ensuring the availability of commodities, including blood as well as medicines and instruments for emergency obstetric and neonatal care, is critical.

Health care worker listens to a fetal heart rate at the Mnazi Moja Health Center (top). Mother and child wait for services at the Mnazi Moja Health Center (bottom left). A child is treated for fever at the Magu District Hospital (bottom right).

Providing health workers with adequate training and continuing professional development, including ensuring that there are well-trained care providers at the remotest sites, remains a challenge. Yet successful U.S.-supported education and mentoring programs exist at several levels. For instance, in Mwanza, the Peace Corps (through the Global Health Service Partnership) has placed seasoned U.S. health providers in teaching hospitals and educational facilities to share their expertise in obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, and midwifery, with local providers.

Through the U.S.-supported Tibu Homa project, pediatric specialists teach staff how to better diagnose malaria and distinguish it from other febrile illnesses.

But training and mentoring programs for health workers in remote settings are not enough. Ensuring that adequate commodities are available throughout the country is also essential. Through capacity-building activities with Medical Stores Department (MSD) staff, the U.S. government has provided technical and infrastructure support to improve the availability of medicines at service delivery points.

At Sekou Toure Hospital in Mwanza, the United States has supported emergency obstetric and newborn care training for providers working on the labor wards. Yet in some cases this hospital and other well-resourced facilities are overwhelmed with patients because dispensaries and health centers are not equipped to manage deliveries, particularly complicated ones.

Although providers at this referral hospital have benefited from training to provide emergency obstetric care, even Sekou Toure faces challenges. The operating theater is some distance from the labor and delivery area, making rapid preparation for cesarean sections during complicated deliveries difficult. At the same time, there is no blood bank at the hospital to facilitate the provision of blood in the event of postpartum hemorrhage.

2.) Programs to expand vaccine coverage have been highly successful, but reaching the most remote populations remains a challenge.

Tanzania has successfully extended immunization programs to all regions of the country, and vaccines for mothers and children are provided free of charge. Tanzania’s success in maintaining immunization coverage above 90 percent and commitment to cofinancing the introduction of new and underutilized vaccines with Gavi support is exemplary and offers a model for the region. The confidence of providers and patients in vaccine programs appears quite high.

Challenges in Tanzania, as elsewhere, include reaching children living in urban, peri-urban, and remote rural settlements.

Magu District must maintain motorbikes and boats to transport vaccines to remote villages and island communities. And transporting vaccines, which must be stored at a consistent temperature, from the central storage facility in Dar es Salaam to the more remote regions, can be a challenge because the Medical Stores Department (MSD) has just two refrigerated trucks.

The United States has been working with MSD to support the development of an electronic records-keeping system to better manage vaccines and other medical commodities. This represents an important step toward anticipating needs at the zonal level, where warehouses may not have enough capacity to store goods long term, and being able to deploy new shipments as stocks run low.

Health commodities and vaccines stored at the Medical Stores Department.

3.) Although not explicitly framed as MNCH initiatives, PEPFAR-supported programs are nevertheless helping to link women and children to other MNCH services.

PMTCT programs are successfully boosting pregnant women’s access to other essential health care services for mothers and children. In Dar es Salaam at Mnazi Mmoja Health Center, which is a national center of excellence for HIV care and training, women and children can move easily down a hall from station to station as they seek antenatal care and PMTCT counseling; receive postpartum family planning advice and HIV treatment; and seek immunizations for themselves and their children. Similarly, at Sekou Toure Regional Referral Hospital in Mwanza, through a series of rooms bordering a courtyard, women can take their children for immunizations and at the same time access PMTCT services and schedule cervical cancer screening, also supported by PEPFAR funds.

Mother and child access integrated health services at the Mnazi Moja Health Center.

At Baylor Children’s Foundation in Mwanza, which partners with the nearby Catholic-run Bugando Medical Center to provide care for infants, children, and adolescents infected with HIV, young patients are immunized against vaccine-preventable diseases. During its visit to the Baylor facility, the delegation also learned about initiatives for “expert mothers” to encourage each other regarding the importance of PMTCT testing for their own health, as well as the health of their children. There are important economic empowerment initiatives for adolescents infected with HIV.

Yet there are still shortcomings when it comes to protecting HIV-positive children’s health: test kit shortages, the facility’s inability to test for viral load to determine the success or failure of children’s treatment regimes, and the challenges of providing treatment for children diagnosed with some opportunistic infections and AIDS-associated cancers. And there are also limits to the extent to which PEPFAR programs can address the broader population’s MNCH needs.

The ongoing PEPFAR refocus on geographic areas with the highest burden of HIV/AIDS, under “PEPFAR 3.0,” raises questions about the sustainability of MNCH gains realized as a result of the PEPFAR platform, particularly if PEPFAR programs are eventually scaled down in areas with lower HIV incidence.

RECOMMENDATIONS TO ENHANCE U.S. ASSISTANCE

With the launch of the Sharpened One Plan and Big Results Now, an enormous opportunity exists for the United States to reinforce its support for Tanzania’s efforts to improve maternal, neonatal, and child health. Often overshadowed by the sheer magnitude of PEPFAR investments, U.S. program support for MNCH, channeled largely through USAID, is a modest but nevertheless critical element of U.S. bilateral engagement on health in Tanzania. Yet despite general bipartisan agreement on the importance of supporting global programs to protect the health of mothers and children—and the magnitude of the need—U.S. bilateral support for MNCH programs has remained relatively flat in recent years.27

Vaccine programs, basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric care training, malaria prevention, diagnosis and treatment initiatives, and PEPFAR-associated MNCH programs have shown impressive results. Efforts must now be directed at consolidating the gains realized; identifying innovative approaches to accelerate progress on strengthening human-resource capacity; and encouraging continued domestic resource mobilization, as well as funding from international partners, for MNCH.

The United States, working with the Tanzanian government and other bilateral and multilateral partners, can help secure MNCH gains already realized while considering ways to help Tanzania begin to plan for securing a place for continued investments in MNCH during its anticipated economic transition.

The United States should continue to partner with the government of Tanzania and support efforts to build capacity to address maternal, neonatal, and child health challenges, as outlined in the Sharpened One and Big Results Now plans. The United States can share lessons learned from its engagement with CHWs in other contexts with the government of Tanzania and find ways to build on the training model embodied in the Global Health Service Partnership to help strengthen human resources for MNCH in Tanzania. At the same time, the United States can strengthen technical assistance programs to help Tanzania gather data to better evaluate current MNCH service providers and facilitate their engagement in continuing professional development.

The reductions in under-five mortality in Tanzania have resulted from high vaccine coverage rates, as well as Vitamin A supplementation and malaria prevention and treatment. That Tanzania, a largely rural society, has achieved such high vaccine coverage suggests that commodities can reach even the most remote communities.

Given the low contraceptive prevalence rate in Tanzania, it is worth examining the success of vaccine programs in raising awareness and extending coverage to remote and rural areas to determine if lessons can be shared as Tanzania prepares to expand access to and uptake of voluntary family planning through the Sharpened One Plan, whether through mobile outreach services, to which the United States has contributed, or through other means. To be sure, there are cultural norms around childbirth and family size, and technical aspects associated with contraceptive storage and use, that make increasing uptake of voluntary family planning different from increasing immunization coverage in important ways. Nevertheless, there may be important lessons in the areas of health education, behavior change communication related to family health, and commodity management that may be shared across program areas.

At the same time, identifying opportunities to integrate immunization and voluntary family planning services may prove helpful in increasing the uptake of voluntary family planning, as well.

PEPFAR-funded programs, such as PMTCT initiatives and pediatric HIV diagnosis and treatment activities, have served as valuable platforms for promoting the access of mothers and their children to a variety of other reproductive, maternal, and child health programs. As PEPFAR undergoes geographic realignment to focus on areas of high HIV burden and “rationalizes” the allocation of partner contracts in specific regions and facilities, it will be important to ensure that the MNCH gains realized as a result of association with strong PMTCT and pediatric AIDS platforms are not “lost in transition.”

In conversations with health officials at all levels, from the MOHSW to Magu District, we heard concerns that the PEPFAR realignment means that the United States is essentially “pulling out,” and that patients in lower-burden areas, like Mwanza Region, might be lost in the process. At one meeting, officials worried that the transition could lead to social instability. Careful communication with the government of Tanzania, with health care providers, and with patients, themselves, as well as planning for the sustainability of MNCH gains realized as a result of PEPFAR programs, will be essential. In the longer term, this will mean strengthening more direct U.S. engagement on MNCH and bolstering support for the Sharpened One Plan efforts underway.

The government of Tanzania’s contribution to total health expenditures in the country is around 8.1 percent, well short of the Abuja Declaration target of 15 percent.28 As Tanzania’s economy grows, more funds will enter the health sector, but there are still large gaps. Tanzania’s dependence on donor financing to support government health spending is unsustainable.

The MOHSW is currently developing a health care financing strategy, which focuses on strengthening health insurance options for Tanzanians. It has a goal of moving toward universal health coverage and rationalizing the patchwork of private and state-run insurance schemes and community health funds that protect a limited number of Tanzanians against catastrophic out-of-pocket spending on health. Currently only children under the age of five, adults over age 65, and pregnant women receive health care services free of charge, yet if Tanzania is to reduce maternal mortality, it must improve women’s health before pregnancy, including increasing uptake of voluntary family-planning services to allow for the healthy timing and spacing of pregnancies. At the same time, protecting the health of women beyond their childbearing phase remains essential. The United States can help share lessons from other countries where it has supported the development of national health-insurance schemes and be a partner to Tanzania to help develop a process for better promoting access to preventive care and treatment services for women from pre-pregnancy through adulthood.

To protect the impressive gains in reducing child mortality as a result of expanded vaccine coverage, the United States can encourage Tanzania to start working with Gavi to establish best practices for the country’s future graduation process and begin building the appropriate mechanisms to ensure a timely and successful graduation. In accordance with Gavi’s graduation policy, when a country’s gross national income (GNI) per capita crosses the Gavi eligibility threshold (currently US$1,580), it enters a graduation process and begins to phase out of Gavi support. During this five-year period, Gavi intensifies its efforts to help graduating countries be in the best position to financially sustain their routine programs and new vaccines.

Currently classified as a low-income country (in 2014, GNI per capita was $630), Tanzania pays 20 cents per dose for the vaccines procured with Gavi support, and Gavi pays the remainder. But with rapid economic growth in recent years, the discovery of natural gas reserves, and Tanzania’s own stated goals of reaching middle-income status by 2025, starting to plan now would give the country time to build a solid foundation for this transition. Once Tanzania completes the five-year Gavi graduation process, it will assume 100 percent responsibility for paying for vaccines. It will be important for the government to develop a long-term plan for strengthening budget support for that kind of financial commitment. The United States can be a partner to the government of Tanzania in planning for the Gavi transition and can facilitate networking with other countries that have already entered, or will soon enter, the Gavi graduation phase, to share lessons from earlier experiences.

LOOKING AHEAD

The United States has multiple opportunities to showcase the strong partnership with Tanzania on MNCH goals and to plan for future engagement as the country prioritizes MNCH within the Sharpened One and Big Results Now plans and anticipates its own economic transition.

These opportunities for partnership include:

- Intensifying support for MNCH activities at the community level and through capacity building and supply chain management.

- Helping Tanzania analyze and share lessons learned from successful vaccine programs with program areas in which success depends on extending services and human-resource development to the community level.

- Carefully communicating about and planning for the sustainability of MNCH gains realized through PEPFAR support as the program is realigned to focus on high- burden areas with high HIV incidence.

- Strengthening the bilateral dialogue regarding long-term planning and domestic resource mobilization for reaching maternal, neonatal, and child health goals.

The eagerness of mothers to ensure the best possible care for their children and themselves is undeniable. Women arrive at health clinics early in the morning, with one child or with several, and sometimes from great distances, to wait patiently to meet with providers, ask questions, and receive advice.

As the world looks beyond 2015 and considers how to build on successful efforts to reduce child mortality and improve maternal and neonatal health, the lessons from Tanzania both offer inspiration and suggest opportunities for enhanced collaboration in the future.